Sexually transmitted infections: The social problem from a social ecological perspective.

The Social Ecological Model is a multilevel health model that clearly depicts how different factors at different levels of influence can impact ones health. I find this to be an easy to understand model and appreciate the many visual representations of it that can be accessed online to provide added clarity. It seeks to remind us that health is not something that is solely within the control of oneself.

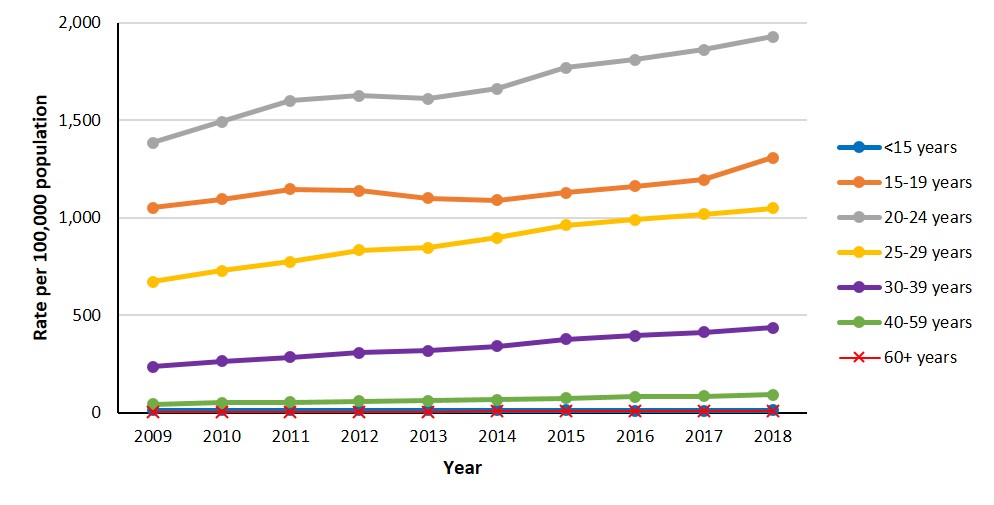

I chose to use the Social Ecological Model to better understand the multiple levels of risks related to sexually transmitted infections (STI’s) and how to address these risks using this multilevel model. I looked at other health models but found that many focus too narrowly on individual health behaviours and do not do enough to also consider the environment, social and political factors. This is also a common oversight when planning for and implementing interventions meant to decrease the transmission of sexually transmitted infections (Salazar et al, 2010). When considering transmission of STI’s in the community, I have broken down the various components of this issue within the different levels of the social ecological model below and have offered suggested interventions that would fit within each level. The intention of any successful health promotion or disease prevention program is that there is impact at all levels of the model for the maximum amount of effectiveness. It is important to note that the transmission of STI’s and their negative health outcomes continues to be a significant public health concern across Canada. Below is a chart from the Government of Canada Report on Sexually Transmitted Infections in Canada, 2018 that shows the increasing rates of STI’s among all populations nationally.

Individual Level:

When considering transmission of sexually transmitted infections at the individual level, we would focus on knowledge, beliefs and attitudes about STI’s and sexual behaviours that may contribute to STI transmission. Interventions aimed at the individual would aim to increase knowledge and understanding about STI’s and how they are spread and would promote prevention strategies. This is the level in which standard education and awareness campaigns related to STI’s would fit. Within the clinic setting or in the community, offering free condoms and other prevention supports and promoting STI testing and vaccination against viral STI’s (e.g. Hepatitis A, B and human papilloma virus) would fit within this level as well.

It is important when planning education and awareness campaigns to consider the target audience. An example of a successful STI testing campaign that I have been involved in is the ‘Check your sausage’ campaign which was a social media campaign geared to gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) and used popular hook up social media sites to get the message out (e.g. Grindr, Squirt).

Interpersonal Level:

This level of the model would consider interpersonal relationships including sexual partners, informal and formal social networks, sexual networks and family and aims to improve communication and promote healthy decision making. Promoting open communication and discussion regarding sexual health and STI risks between sexual partners would be an intervention that would fit here, as would providing relationship and consent education in schools to adolescents and educating parents on how to talk to their kids about sex.

Organizational Level:

Addressing sexually transmitted infection transmission at the organizational level means ensuring that health care settings and organizations that support clients at risk of STI’s are welcoming, supportive and as barrier free as possible. Working to ensure that the sexual health clinics are inclusive and gender affirming places to access sexual health care would reside in this level of the model.

Looking at how to work together with other community partner agencies to improve health outcomes for clients would fit here as well. Public health departments in Ontario and their local AIDS service organizations (ASO’s) routinely work together to implement education initiatives and co-led testing services in the community. The work our sexual health clinics are doing to implement the 2SLGBTQI+ Health Equity Best Practice Guideline from the RNAO would fit here as well.

Additionally, provision of comprehensive and stigma free sexual health education would fit within this level as well as community and even societal/structural depending on which locus of decision making and control you are looking at with respect to the education sector. In York Region, we work closely with the local school board curriculum consultants to develop tactile, interactive and simple activities that educators can do in the classroom to teach the sexual health components of the health and physical education curriculum.

Community Level:

This level looks at whether the community environment supports or detracts from the health outcome being looked at. Making sure access to our services are as barrier free as possible with respect to the community is important. Are services located in many areas of the Region – are they accessible to those with physical disabilities? Are services offered in multiple languages? Do 2SLGBTQIA+ clients feel comfortable accessing services here (Baral et al, 2013)?

Provision of mobile health clinics is an intervention that would fall within this level. Also, offering outreach services to marginalized populations would be a community level intervention.

Societal/Structural Level:

Having policies in place that allow all people to access sexual health services regardless of income or OHIP coverage would fit within this section of the model. Also, advocacy to improve services for populations with barriers would fall here. An example is supporting those who work in the sex trade to be able to access care without fear of legal reprisal. Another example is to implement comprehensive inclusive sexual health education in all schools.

Training staff who work with clients at risk of STI’s to provide inclusive, stigma free, gender affirming and culturally sensitive health care and to work collaboratively to address the stigma that still exists within the health care system would be societal level interventions that would profoundly impact STI rates and the negative health outcomes associated with them.

These levels are not independent of the others and many interventions will span more than one level depending on its characteristics. It is generally understood that interventions within the individual and interpersonal levels are usually easier to implement but have less effect at impacting population-based health outcomes, whereas interventions in the societal, community and organizational levels have farther reaching impacts, but are more difficult to achieve. All levels are important and to be effective at sustaining behaviour change and health system change, one must consider activities and interventions within all levels of the social ecological model.

References:

- Karches K, DeCamp M, George M, Prochaska M, Saunders M, Thorsteinsdottir B, Dzeng E. Spheres of Influence and Strategic Advocacy for Equity in Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 Nov;36(11):3537-3540. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06893-4. Epub 2021 May 19. PMID: 34013471; PMCID: PMC8133515.

- DeCamp, M., DeSalvo, K. & Dzeng, E. Ethics and Spheres of Influence in Addressing Social Determinants of Health. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2743–2745 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05973-1

- State of Hawaii Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion page

- Baral, S., Logie, C. H., Grosso, A., Wirtz, A. L., & Beyrer, C. (2013). Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC public health, 13, 482. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-482

Laura F. Salazar, Erin L. P. Bradley, Sinead N. Younge, Nichole A. Daluga, Richard A. Crosby, Delia L. Lang, Ralph J. DiClemente, Applying ecological perspectives to adolescent sexual health in the United States: rhetoric or reality?, Health Education Research, Volume 25, Issue 4, August 2010, Pages 552–562, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyp065